El Farellón Printing Press

If faith can move mountains, it can also keep them from moving.

Conversation with Ramón Muñoz Cárdenas.

Visit to Coyhaique

Last year, around this same time, I visited Coyhaique, in Chilean Patagonia. I had to go to the Cemetery of the Island of the Dead in Caleta Tortel to document the epitaph on a cross for a typographic rescue project. These kinds of trips are my favorite because you surrender to whatever may happen. Among the many things that happened, one day, while accompanying my friend Roco to a downtown bookstore, I saw a new edition of the Silabario Hispanoamericano by Adrián Dufflocq, a classic early learning book used in Chile to teach reading and writing.

I asked the saleswoman about the price, and she told me no one buys the silabario. At that moment, my friend Roco, already familiar with the saleswoman because he had been buying many materials for an exhibition he was preparing at the Regional Museum of Aysén, mentioned that I was a typographer.

"A typographer?" she asked.

I knew the question was because typography is an old technology and no longer a common trade.

"Yes, I design letters on the computer," I replied, anticipating her doubt.

"How lovely! Then you must go around the corner to El Farellón Printing Press," the saleswoman worked her magic.

I went searching for the print shop, which was on the same block. I entered a workshop—it felt like a cave, with machines and walls full of papers—and saw a man working there. Sometimes, words flow out of me too quickly, and other times I don't know what to say. This time, it was the latter. I didn't know how to start the conversation. I stood at the door, observing the old machines, trying to figure out what I was seeing. Then the man greeted me, and I simply asked if I could visit him the next day.

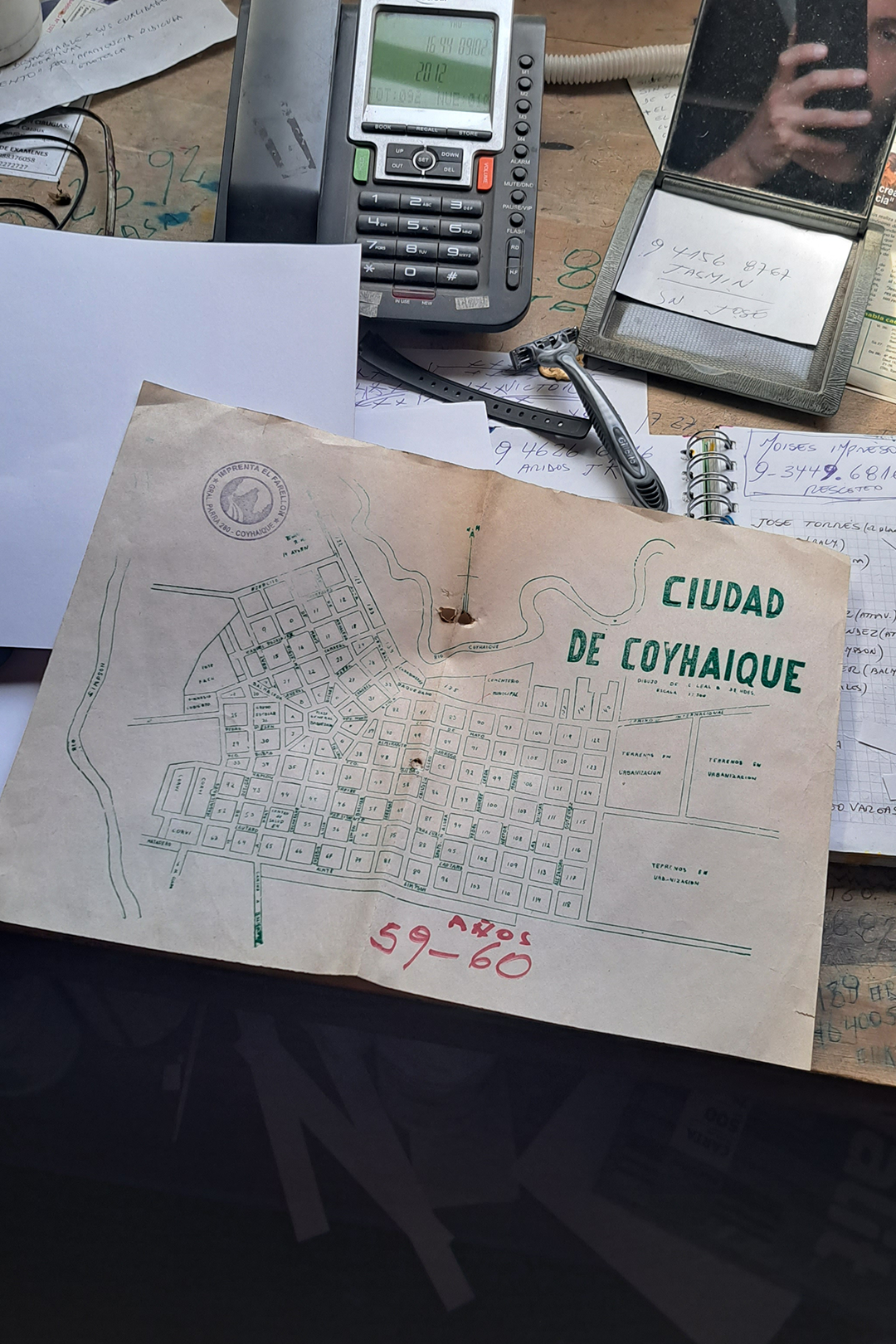

To give some context, Coyhaique is two and a half hours by plane south of Santiago (1,300 km); it's like going to Buenos Aires (1,100 km) or a three-day journey by land and sea, though that's another story. It was founded by pioneers on October 12, 1929, initially named Baquedano, and in 1934 it was renamed Coyhaique. So, it's a relatively young city. The pioneers aimed to build a nation, make use of the land, extract resources, build homes and streets...civilize. Civilization in those years was not conceived without the church and a printing press.

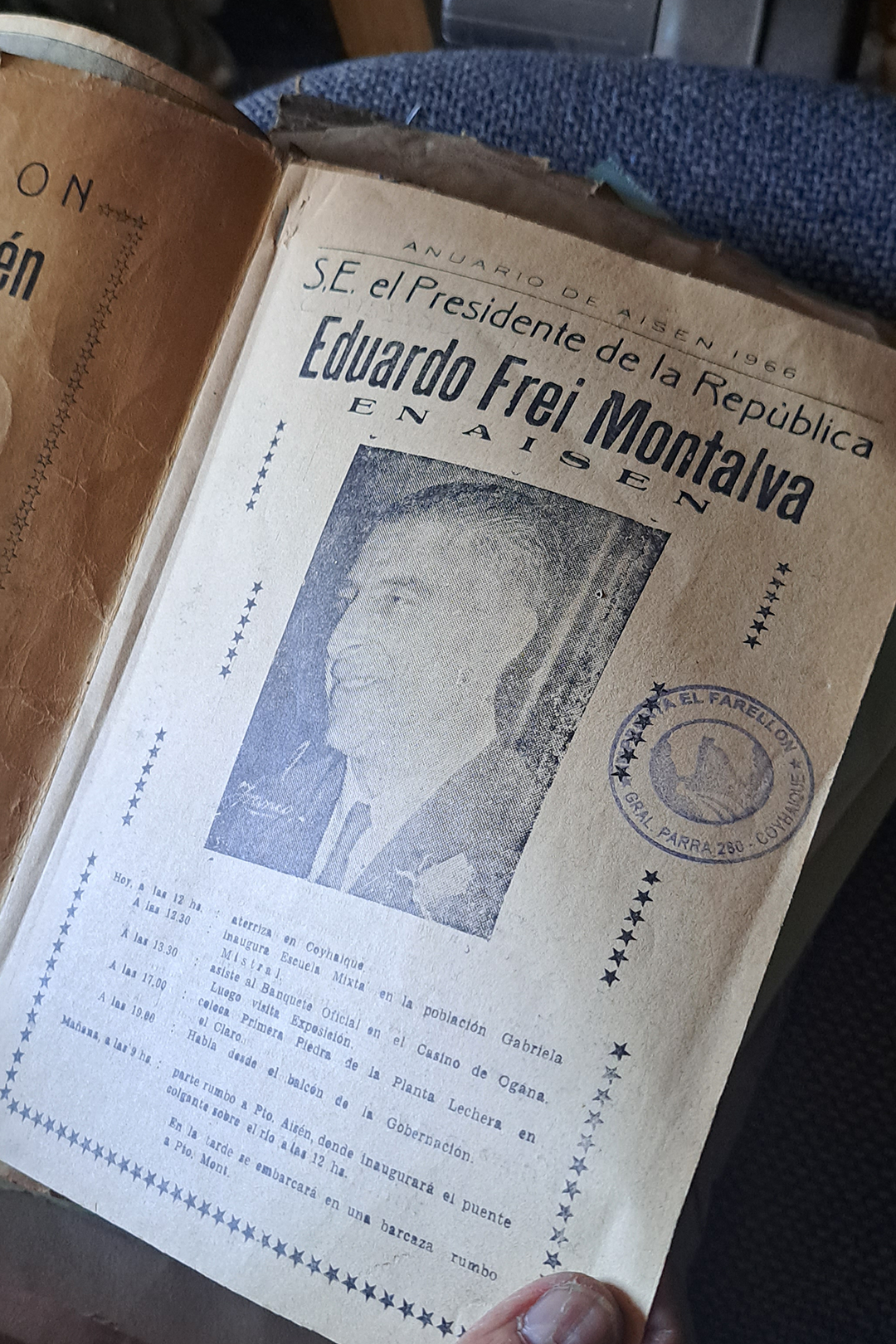

El Farellón Printing Press

The next day, I was welcomed by Ramón Muñoz Cárdenas, who was 73 years old that day, 74 by the time I'm writing this. I started my endless questions. Ramón was born in Chiloé, in San Javier, across from Dalcahue. In 1954, his family traveled south towards Comodoro Rivadavia, Argentina, drawn by the promises and dreams born from the progress of the oil boom. They stopped in Coyhaique and stayed.

Ramón started working at El Farellón Printing Press at age 15. The print shop was founded by the Vicariate of the Servants of Mary of the Catholic Church on October 12, 1962, by Father Alfonso Massignani, who was Ramón's mentor. The goal of the print shop was to produce a newspaper and assist with evangelization, the two classic purposes of printing presses. Over time, Ramón took over management. He continued with the original team, but as digital technology rose, the print shop declined, reducing its operations to just him.

Ramón told me that there was a time when they were in high demand for work: prayer cards, graduation keepsakes, announcements, cooperative statutes, political materials, and poetry books. When the work declined, the letterpress print shop survived thanks to the Internal Revenue Service for printing receipts, invoices, and purchase orders. Those continued to be printed with clichés and movable type. Now, as Ramón says, everything is computerized.

I was there for the letterpress workshop, so I kept closely observing the machines, which had become somewhat ineffective shelves for other workshop materials. Ramón noticed, showed me the machines, and turned on a motor. I usually see this as a ritual of initiation, an opening to detail, secrets, memory, and also, to the magic of the journey.

The workshop walls were full of images, photos of workers, keepsakes, prayer cards printed there, photos of people who were part of the print shop's history, photos of Ramón's motorcycles, and photos of the Artes Gráficas team. Imagine, a group of typographers so large they could form a team! And three machines—two Italian and one Chinese.

"Time has stopped here," he told me. "As you can see, the workshop looks almost the same as it did on its first day. The floor was dirt, but we added cement in some areas because of the mud. The first machine arrived, was placed here in the center, and the workshop was built around it. The machine was never moved again. Now the church wants to turn this into a museum. They've already told me I have to leave, but I've been prepared for that."

Faith and Progress Move Mountains

To me, a farellón was no different from a mountain, but a farellón is a unique rock formation that juts out from the sea or land. Outside Coyhaique, on the road to Puerto Aysén, there is a farellón. It's so prominent in the landscape that it inspired the name of the newspaper: El Farellón.

Farellones, relatives of mountains, shouldn't move. Hence the saying that faith moves mountains, though in reality, mountains do move—it’s just that we speak in human time units. Mountains have always moved, just at a speed the human eye can't detect. Another way to move mountains? Machines, cranes, and explosives. Give the order, and the landscape can change in days.

I was saying goodbye when I noticed a cross with a purple ribbon. Ramón told me it was a piece of the cloak of the Saint of Caguach.

"Protected. That's why this print shop has lasted so long," I said.

"Protected," he replied, "because they haven't been able to move me. This story is long. They've tried to evict me. They've tried to sell the print shop. I've stayed over time. So you see, sometimes faith moves mountains. Those without faith who go their own way—they don't do well. But those who have God in their lives, nothing can bring them down. I know because I've lived it. But now, in March, this place will close."

I think about the saying. I think about the mountain moving. In this case, El Farellón closing. Maybe the saying makes more sense this way: "If faith can move mountains, it can also keep a mountain from moving." Or, "If faith can move mountains, maybe it can keep El Farellón from closing."

The idea of a museum is a good one, but only if the machines keep printing.