The dead will always be there

We went to the General Cemetery in Santiago, Chile, to speak with the marble carvers of Marmolería El Nazareno, located at 584 Valdivieso Ave.

Photographs by Diego Reyes

Located in the neighborhood of Recoleta, the Santigo General Cemetery is one of the oldest and largest in Latin America. For over 200 years it has housed the remains of more than two million people, spread out over 86 hectares. Cemeteries are museums; places where history, various styles, techniques and fonts endure through time.

I had been meaning to go there for a while to look at hand-carved letters, perhaps in part to take a break from working on the computer. I knew the marmolerías (shops where hand-carved headstones are made) were near the subway, right by the main entrance to the cemetery on Recoleta Ave. I made plans to go in July. After a visit to the Memorial to the Disappeared, I made my way to Valdivieso Ave. I was hoping to speak to one of the old craftsmen who work with marble, to watch someone who had mastered the technique at work.

A man at one of the last shops on the row asked if he could be of assistance, motivated either by a potential sale or by the excitement on my face as I watched the carving process.

–What do you need? Can I help you with anything?

–Ummm, yes. I'm not sure where to begin, though – I replied.

Don Ruben quickly caught on that I wasn't there to visit the departed. We chatted for a while outside his shop and I was soon invited in to look at pictures of his father, the first of four generations of carvers in his family. Since his own son and grandson were working at the shop that day, I got to see them all at the same time.

The idea was to introduce myself that day and then come back when I had time for a longer conversation. My first visit to the marmolerías had no particular destination, but the second time I went straight to El Nazareno, located at 584 Valdivieso Ave. I was expecting to find Don Ruben, but I ran into his son, Alejandro Neyra Cirano.

After reintroducing myself, I reminded him that I had been there two weeks earlier and that I wanted to interview him.

–We can talk while I finish up this job.

I also asked him to make a piece for me. When he asked me how I wanted the letters done and I said chiseled, I saw his face light up, because chiseled letters are no longer a common type of commission.

–Ok my friend, let's talk while I'm not busy –he tells me, setting aside the carving he was working on.

–My grandfather was carving back in the 40s. – he shows me the same photo that I had seen earlier – That's four generations and counting.

As he takes a phone call about some nearly finished commission, I reflect on how challenging this line of work must be sometimes.

–There, all set! –he says once he gets off the phone.

Is it hard, working with people who are going through this? We're talking about grieving families here.

–In a way, you have to use a little psychology to "diagnose" the person. Say someone comes in who recently lost a child. We are prepared to bury our parents, but never our children. You have to speak to them very tactfully.

Do people order the tombstones in person or do they send someone else to do it?

–They come in person. If they come for a restoration job, they have a much more relaxed attitude. My dad was a big drinker. Can you carve him a little wine glass? People will ask for anything.

They have already dealt with the loss.

–Sure, it is a part of living and at some point, you get over it. We have worked for fathers and mothers, for sons and daughters, friends, celebrities, for the families of disappeared prisoners. We are all going to lose a loved one eventually.

How long have you been working here?

–Since I was 16, just like my son. I have been doing this for 31-32 years, but my whole life has been lived among stones. I am a third-generation stone mason, and now my grandkids are around here somewhere, playing with the mallet (a special hammer for chiseling stone) and chisel.

The chisel is the what counts.

–Sure, like Michelangelo. Now you get to show off –says his son, Sebastián.

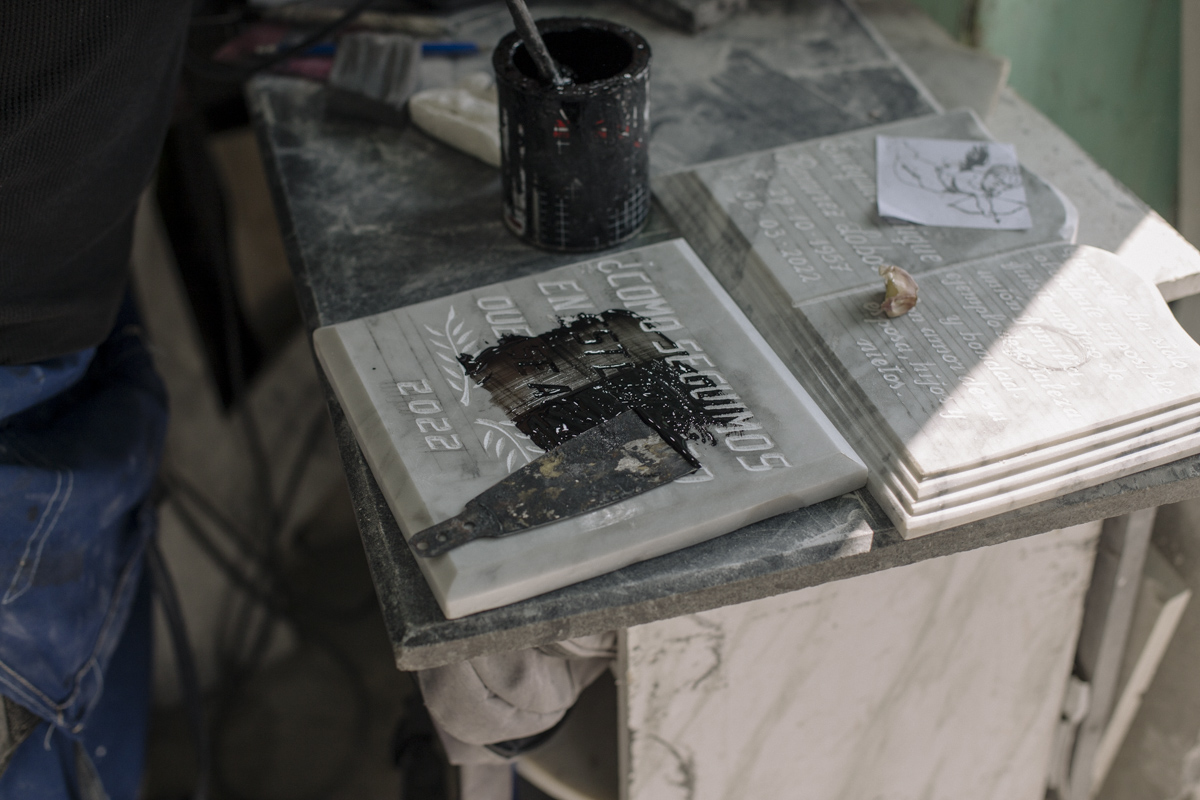

I write a sentence in freehand on a piece of paper he gave me. "How do we go on in this world that is ending? 2022". The phrase has been on my mind these days. I write it in the same handwriting I would use to write down a name, some directions I got on the phone or the grocery list. Sebastián asks his dad if he wants to hear Camilo Sesto, but Donde estés, con quién estés starts playing before an answer even comes back.

Do you like working to specific music?

–In the morning we play motivational music, Tecnotronic, but you still need to focus because the centimeters are all in your head. You need to calculate how to distribute the letters inside the space.

With those words, he takes a piece of paper and makes two marks, one to measure the height of the letter and the other for the interline spacing. He then marks a point at the beginning and another at the end, then come the lines. After that, he uses a triangle ruler to make the grid for the letters. This is only meant to be a sketch to calculate the spacing of the letters, but he does it with a precision that suggests the carving is already designed and he is simply bringing the letters embedded in the marble up to the surface. He marks a letter, then a space; letter, space, letter, space. The ratio is four spaces per letter, with the exception of the M and the W, which are wider and require an extra space, and the I, which needs a single space.

–I'm going to put some twigs in there so they don't look so lonely –Alejandro tells me.

I watch him work in silence, observing the precision with which he makes the letters. I try not to distract him at all. There is a beauty to witnessing a master craftsman with 30 years of experience at work.

It's easy to erase the grid because it's just graphite pencil, but what happens when you make a mistake in the carving? Or do you not even make mistakes anymore?

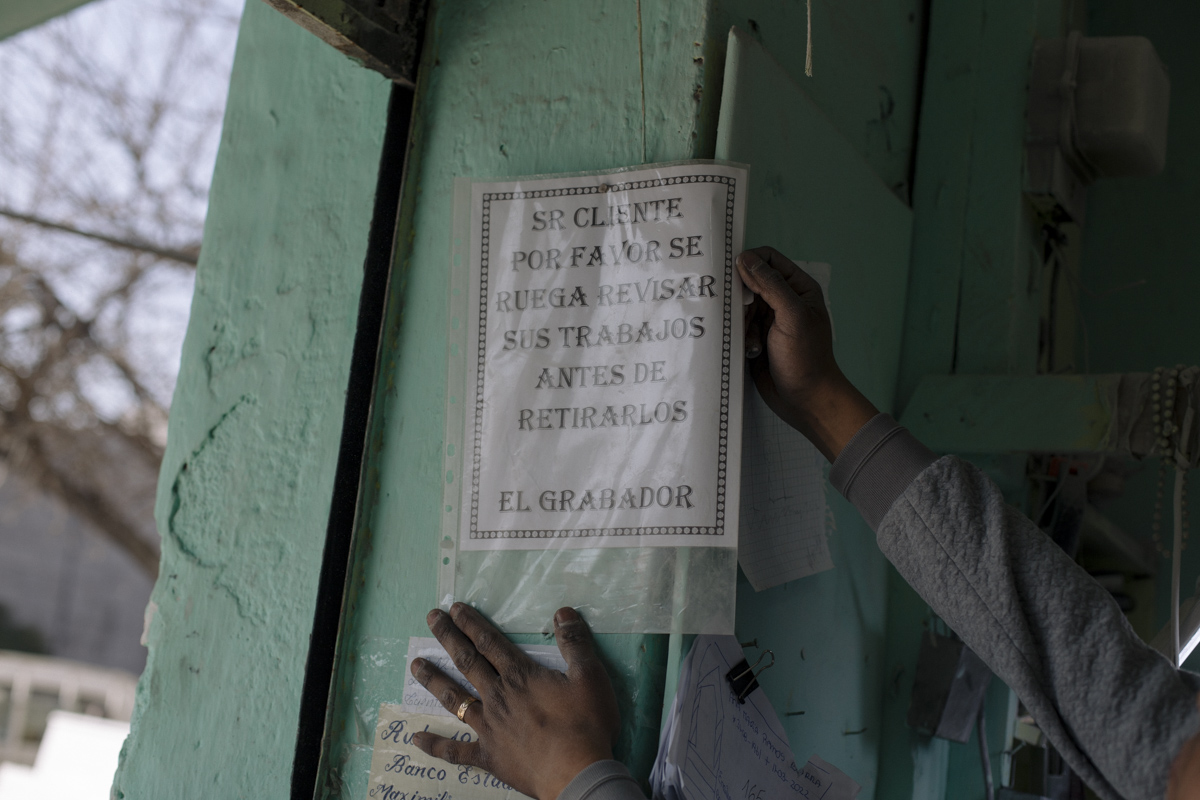

–You have to make a small reduction. There is always enough stone for it. And you do make mistakes: you get distracted, customers show up, they start talking and you miss the cut. You need to focus and try to keep calm, because some customers can get on your nerves.

Another member of the family joins us at this point: Maximiliano, one of Alejandro's other children. He works with marble as well, preparing the stones that will later be carved. He gives me a quick primer on various types of marble. They mostly work with Carrara marble because it has fewer veins, but there are other types of marble with their own colors, named for their place of extraction, such as red Verona marble. I learn that red marble can be found in Chile, around Vallenar, but that it is very expensive and difficult to source, and it is easier to bring the stone from Italy. There are also the natural formations known as Marble Cathedrals in protected areas, as well as Travertine stone, which is a similar to marble but less prized. Maximiliano tells me that the marbles used in cemeteries are Carrara, brown Emperador, green Ubatuba and black Brazil.

–Ok my friend, let's get down to business. This is my favorite part –says Alejandro, reaching for his mallet and chisel.

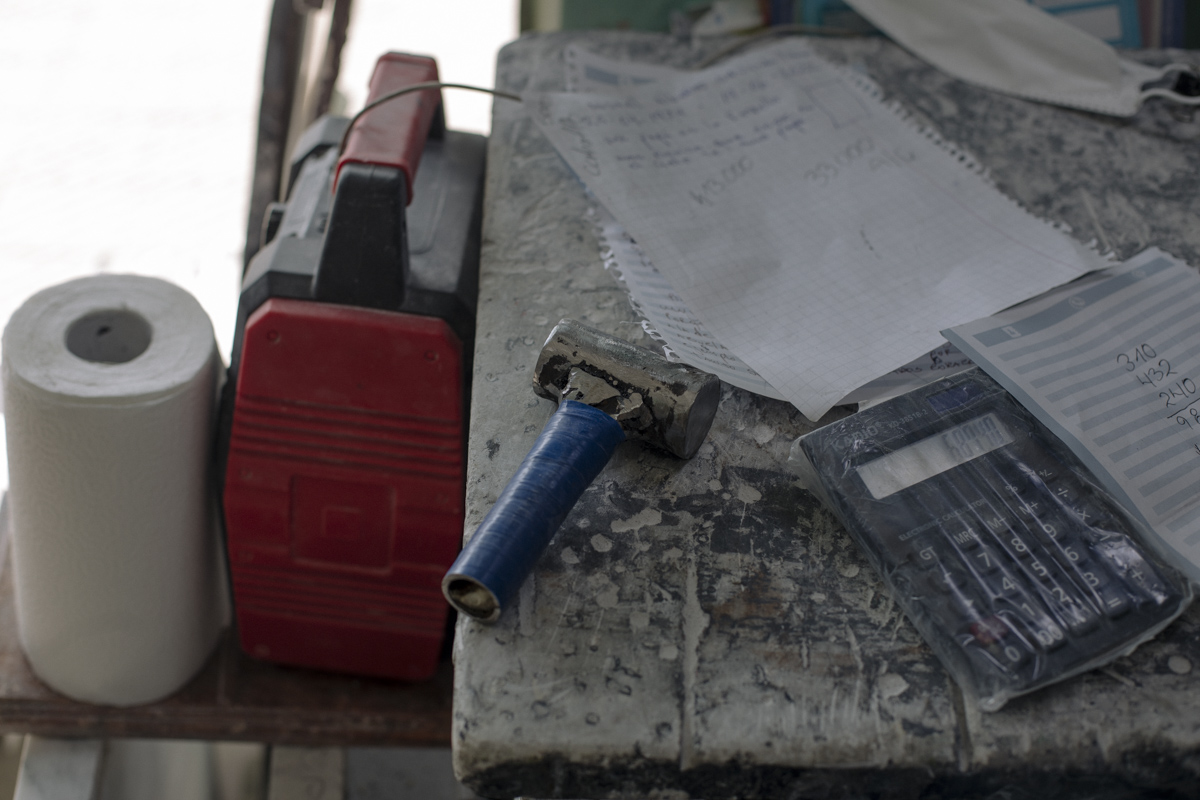

It was at this point that my friend Diego noticed a head of garlic among the tools in the workshop. As it turns out, garlic is essential to the sketching process. The marble is rubbed with garlic until it is coated in a layer thick enough to scratch with a pencil. Without this coating, the smooth stone surface is impossible to draw on.

Alejandro begins by chiseling all the horizontal letter segments, as he tells us about his past struggles with addiction. His tool bag was stolen, which marked the start of that dark period. Out of all his expensive tools, he regrets the loss of his mallet the most: it was a gift from his father to encourage him as he learned to carve stone, which he had used for 28 years. He was fond of feeling its weight in his hand.

Chiseling letters is a slow process. Before engraving machines became common, a hard-working craftsman could hammer out 1200-1500 letters, he tells me.

–Not to sing my own praises, but I am (or was, at one point) one of the fastest chisel engravers around. My colleagues would do 1000 or less. Using a machine, I can do 5000 or 6000 letters.

While typing out this interview, I re-read that statement and count the letters I have used so far: 6566 without breaking a sweat. I think about the way he had to hit the chisel to make a small line. First, he made all the upper horizontal marks of the strokes, then the lower ones. Each line of the letter is made up of two cuts that form a V. Once the horizontal lines were done, he started on the vertical ones. It didn't take long at all.

Is chiseled writing much in demand nowadays?

–No. People ask for it when more relatives die and they need to add a name to the headstone, then you need to match the lettering style.

Is there a noticeable difference between craftsmen?

–Yes. A nice letter has to be V-cut, that's where the craftsmanship shows. I can recognize my father’s and some of my colleagues’ work by their technique.

Has the quality gone down since engraving machines came out?

–The letters look just as good, but they end up a bit shallower. Striking the marble leaves a deeper imprint.

Are there any especially difficult letters?

–I don't think any letters are harder to do, they just require more cuts.

Sebastián thinks there can't be more than 50 people in Chile who work using this method. He's eager to learn it himself. If the power goes out, he's screwed, Alejandro says, as he keeps hammering away at the sign I commissioned. First it was the Dremel, now it's the laser cutter. He points to a laser-cut statue of the Virgin Mary, standing next to an identical copy. The repeated images create an instant feeling of cold emptiness. The carvings here show no sign of a human touch. They are all just standard issue. And if a standard figure of the Virgin was not enough, there are standard headstones with her image on them now. Sebastian tells me that people prefer the laser because they always want the best for their dead, but I just wonder, what makes laser cutting better?

There is real beauty in the carved letters Alejandro is finishing up. I am surprised by the weight of the marble when he hands me the piece. I knew stone would be heavy, but I was stil shocked. Its weight seems to add to the solemnity of the ritual of death. This is a good job –Sebastián tells me as I ponder the thought–, the dead will always be there for us.

You can visit marmolería El Nazareno at 584 Valdivieso Ave., Recoleta, Chile.