The future is always lit by neon

An interview with master neon worker, Helio Méndez.

Protographs by Diego Reyes.

I met up with Helio Méndez on a summer day. His workshop is located at 3824 José Joaquín Prieto Vial, San Miguel, in Santiago, Chile. Helio is 55 and has been in the trade for the past 35 years. His workshop, where we had our conversation, was founded in 1987. Although he cites that year as his official start, he learned his craft from childhood, as if he was destined for it. His father was in the neon sign trade, and was so enamored of it that he named his firstborn Helio (Spanish for Helium) Argon, after two noble gasses that work well together. The child, however, passed away and the name, along with the business and the craft, were passed on instead to our Helio, his younger brother, as if by royal lineage.

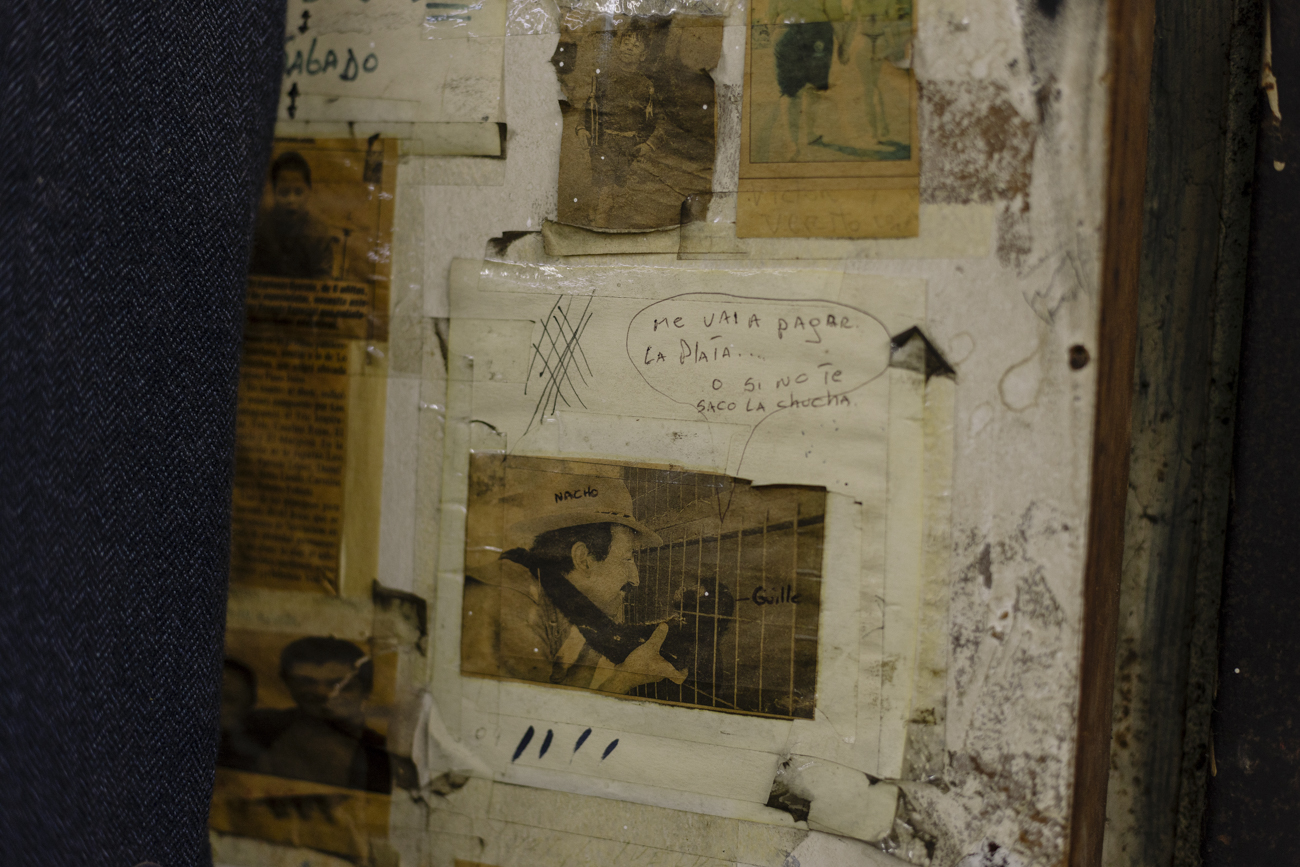

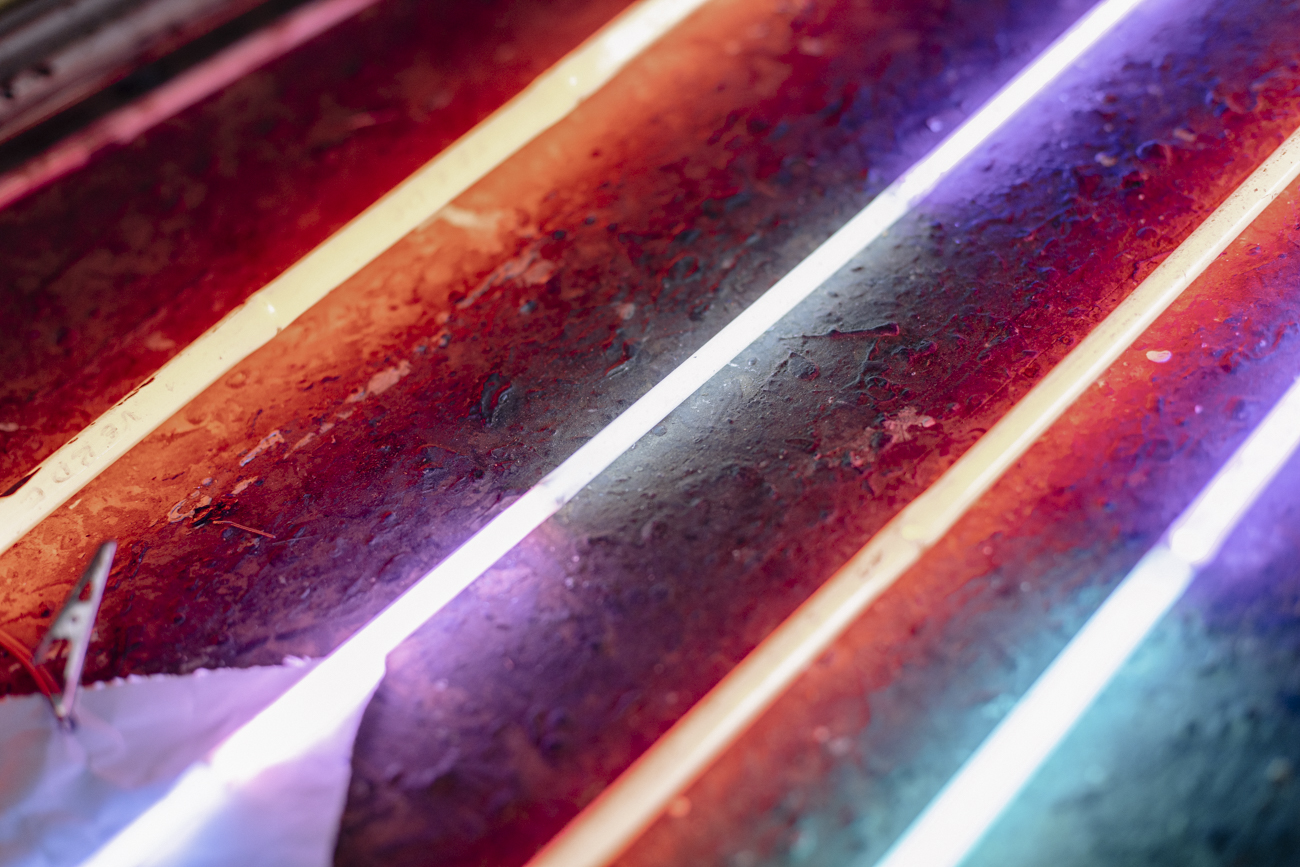

Neon signs are made of glass, a fragile material that must be handled carefully to avoid breakage. This characteristic makes them less competitive than their upstart rival, LED. However, as those with a discerning eye will know, there is no comparison between LED light and the deep, sensual vibration of neon. There was a time, some 20 years ago, when this work was in high demand. Orders flooded in and repairs had to be done overnight when needed, which was common for this type of signage. Although there were many other shops, there was plenty of work to go around for everyone. Today, Helio works in a space that seems to exist outside of time. The walls are papered with posters ranging from Boric to Allende, "so no one is offended", he tells me. The workshop is divided, broadly speaking, in two sections: the burner area and the area where the vacuum pump is.

While we talk, Helio is getting the burner ready to work on a sign for a cafe. Before it can be worked on, the glass is heated to 660° Celsius with a blowtorch that stays on through the day. Once the glass reaches the right temperature, it can be bent into shape for writing. With skill acquired over years of work, he eyeballs the measurements. Helio and his partner, the workshop's sole occupants, know each other so well that they have the same writing style or "hand", as it is called in the signage community. When they work together on a word, they take care to maintain a uniform handwritten structure. Although there are several ways to achieve uniform shapes, they always aim to make the letters the same size. Since neon writing is three-dimensional, in addition to writing from left to right, they must also account for depth. The words are constructed as a single piece, taking advantage of the full length of the material, and more tubes are welded as they are needed to achieve the full extension of the word.

Helio works with two types of letters: joined and separate, or handwritten and block letters. Of the two, he prefers the handwritten style because it allows for more flexibility, and he says as long as it looks straight it's all good. On the other hand, with block letters, mistakes are very noticeable because they must have the same height and a similar width.

It was a hot summer's day when I went to see him. Helio told me: "In summer I work from 7am to 2 pm. to avoid the heat, but if it catches me, you just have to take it ... drink water and sweat your way through it". The workshop cannot be cooled down because temperature changes can cause the glass to break. Things vary depending on the season, however. "This is a dream job in winter", he says. I can imagine how comforting it must be to work around the fire then. As I write this in the fall, I think back on it with a bit of envy.

Helio used to buy glass and other supplies in Argentina, until he decided to start importing them directly from China. He formed a partnership with other neon workers and contacted a Chinese supplier until he found everything he needed. The Chinese have everything: glass, leak detectors and electrical systems. They have a wide range of better quality materials. Helio has studied and mastered all this. “There is more, better technology available now”, he tells me, “but what is lacking are heirs to the trade. Those who follow in our footsteps will be in a great position, he says, because the Chinese haven't invented a machine that can bend glass yet”.

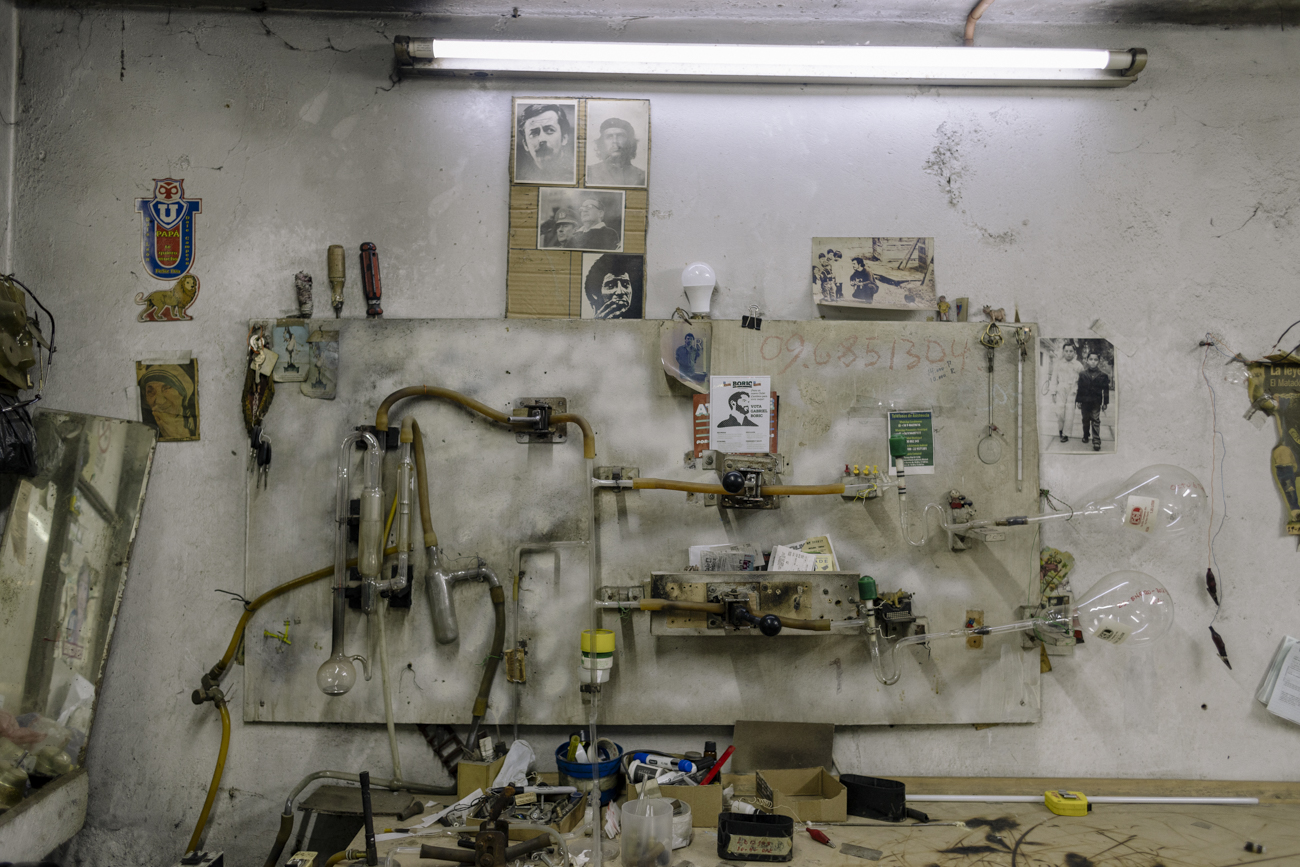

When I first approached Helio, I thought it would be fascinating to watch him bend glass, but I didn't realize that the process of filling the glass tube with gas would be just as interesting, if not more so. When the moment came, it was like an applied physics and chemistry class taking place in a mad scientist's lab. In his workshop, there is an apparatus mounted on the wall that allows the tube to be made vacuum-tight, then filled with gas and mercury, and finally sealed to make it work. The full process goes something like this:

1. The glass is bent over an open flame at 660° Celsius.

2. The design is made while the tube is being heated.

3. To cut the tube, a separate, cold piece of glass is used.

4. Once the design is ready, it moves to the vacuum pump and filling machine.

5. The vacuum is created to eliminate the "common" air within the tube.

6. Neon gas (or a different type of gas) is added, along with mercury. (Helio takes the mercury in his bare hand, and I remember my mother telling me never to do that).

7. The type of gas determines the different colors, but they can also be simulated by using white light inside a colored tube.

8. The tips are sealed.

9. The electrode emits a current, which triggers a process of ionization, electron collision, excitation of the atoms and finally light emission.

Another important part of this visit relates to how I came to know Helio. We met through Alejandro Neyra Cyrano, a master marble carver I interviewed previously. I initially assumed they became acquainted through their trades, as they both work in areas related to lettering. However, they share a common past connected to addiction. They met in rehab. Helio tells me that at one point he lost everything due to alcohol, but while in rehab he realized that that year had presented him with a unique chance to get to know himself. When he got out, he had the tools to cope with almost any problem. He went out and fixed up his yard and the second floor of his mother's house. He tells me that he is putting glass in the ceiling of his room so he can see the stars. If you ask me, he is becoming a master of life as well as neon. He now acts as a mediator in his family's discussions, using the tools he learned in therapy. “I'm enjoying things now that I never did before”, he says. The life of a recovering addict is filled with reminders of the past.

Talking to Helio feels like meeting a character from a book of short stories. Beyond just his mastery of his craft, I admire his strength and optimism. As the poet Teillier would say, Helio is nostalgic for the future. He is always optimistic and believes that the age of neon is yet to come. He outlines his vision in clear terms: "Movies set in the future are always lit by neon". It is an image that I would like to see come true.

You can visit Helio's workshop at 3824 José Joaquín Prieto Vial, San Miguel, Santiago, Chile and contact him at +56 9 9209 4410 to order a neon sign.